- This document is part of the MEV sequencing protocol package:

- http://artic.network/mev

Alignment and Phylogenetics

1. Introduction and background

This resource provides guidance for public health laboratories and researchers performing downstream analysis of measles virus (MeV) genome sequences. It is intended to support routine genomic epidemiology workflows and outbreak investigations. For broader context and applied use cases, please see our companion resource on MeV genomic epidemiology.

Numerous high-quality resources exist for analysing virus genomes that can apply to measles virus; rather than duplicating already existing documentation, this guide highlights commonly used approaches, points to relevant external documentation and outlines a typical analytical workflow.

This is not a comprehensive step-by-step protocol. Instead, it is intended as a practical reference to support analysis, highlight best practices, and indicate where additional guidance may be required.

2. Initial quality assessment of MeV sequences

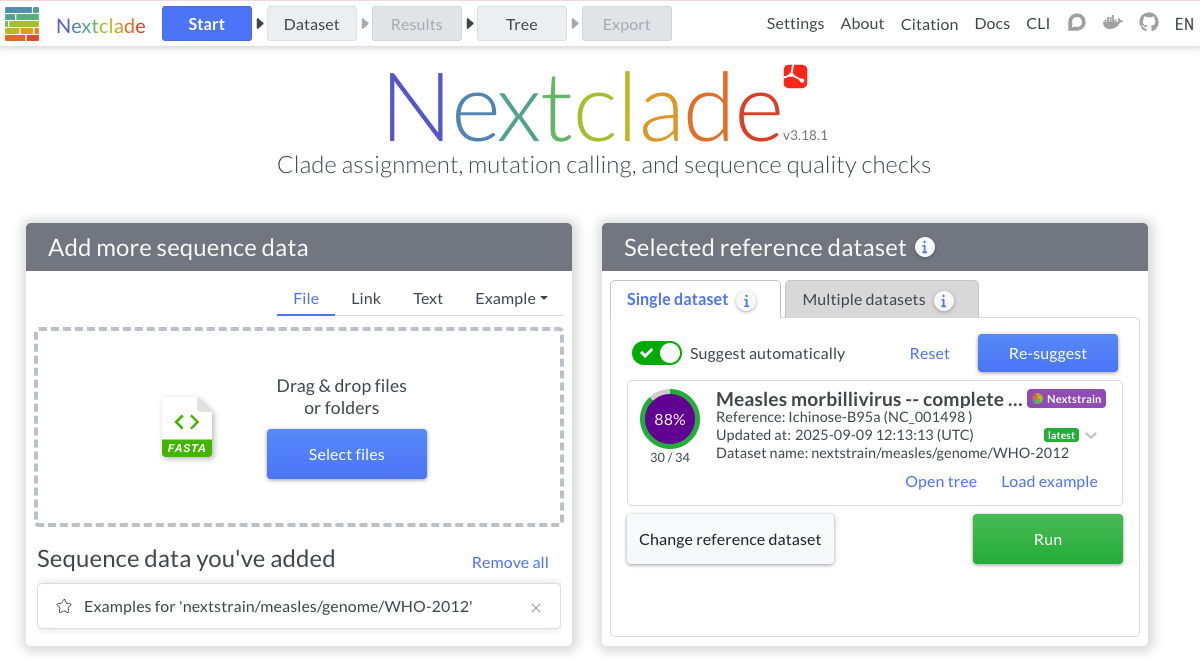

As a first step following genome assembly or consensus generation (for example, after running amplicon-nf), a rapid assessment of sequence quality and placement can be performed using NextClade. NextClade includes built-in MeV reference datasets for both whole genome MeV sequences and the N450 region.

Simply drag and drop the consensus genome file from amplicon-nf to the browser window to run a quick assessment.

Note: All analyses are performed locally within the browser; sequence data are not uploaded to a remote server.

Comprehensive documentation describing the NextClade output is available in the official NextStrain documentation, including a detailed description of the underlying algorithm.

NextClade allows export of both a multiple sequence alignment and a maximum-parsimony phylogenetic tree. However, if greater control over alignment parameters or tree building methods is required, or if independent phylogenetic reconstruction is preferred (e.g. for confidence in results or for publication), continue with the workflow outlined below.

3. Background dataset

A central objective in genomic epidemiology is determining how newly generated sequences relate to existing global diversity. Accurate interpretation depends on access to representative, openly shared genomic data from multiple regions.

It is important to recognise that global sequence availability is uneven and influenced by differences in surveillance capacity, sequencing infrastructure, and data-sharing practices. Interpretation of genomic data should take this into account. Phylogenetic proximity should not be interpreted as definitive evidence of geographic origin. Nearest neighbours in a tree may reflect sampling and reporting biases rather than true transmission pathways.

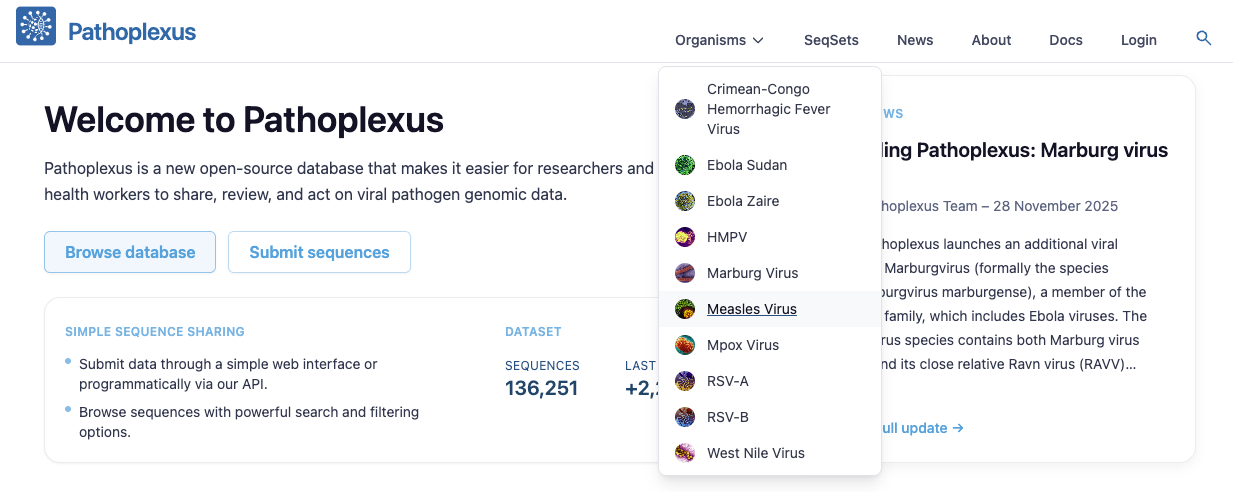

With that in mind, it is important to contextualise your new data, both with data generated locally and also around the world. For measles virus, Pathoplexus can be used to access contextual genomic data. It has a dedicated measles database linked to INSDC records, but also contains data that may not yet be released to INSDC. NCBI-Virus can also be used to accessed solely open-source MeV records from INSDC.

Instructions for account creation, data access and submission procedures are available through the Pathoplexus documentation.

4. Alignment

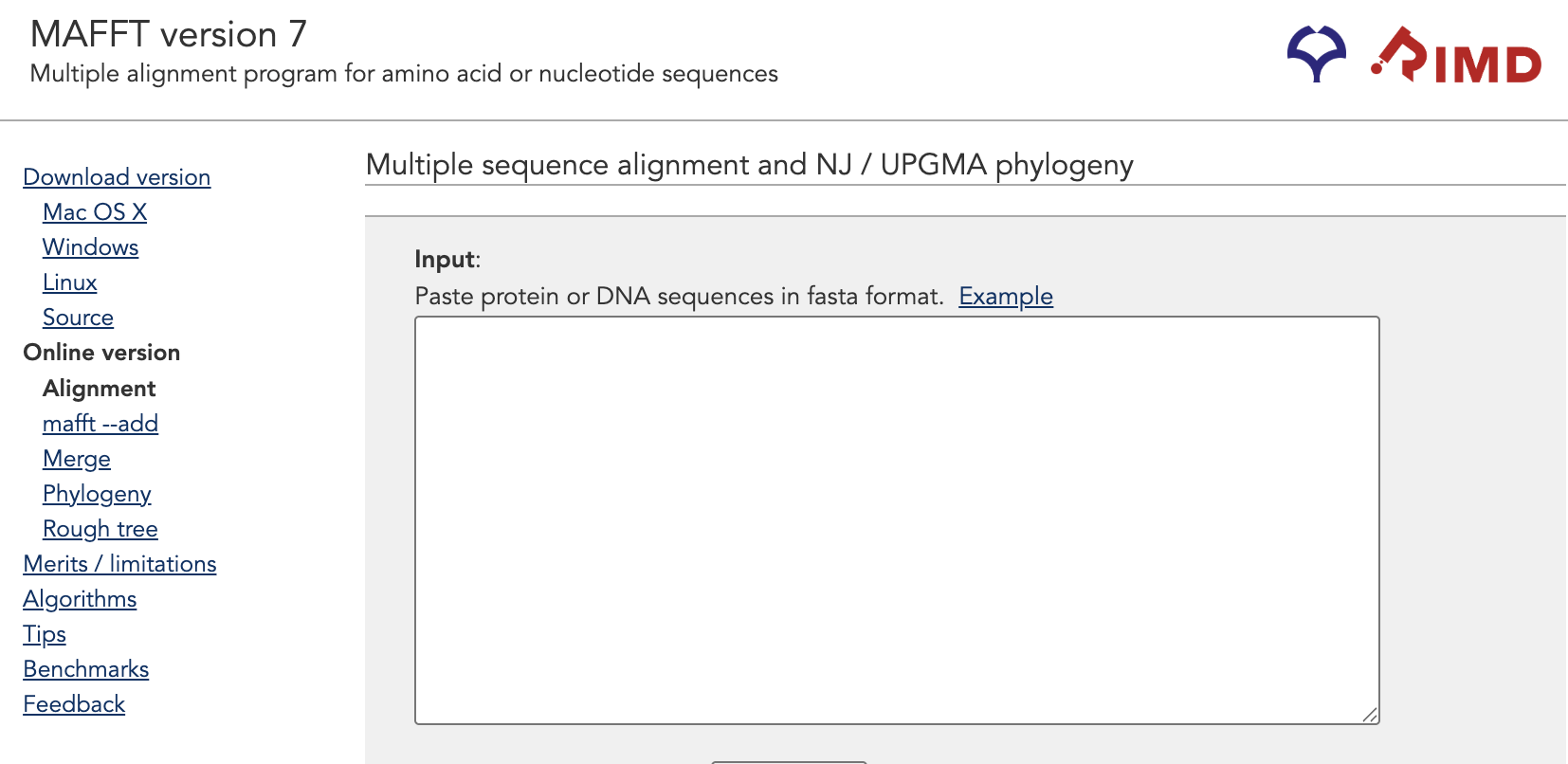

Several established tools are available for generating multiple sequence alignments, and the optimal choice may depend on dataset size and analytical objectives. For viral genome data, MAFFT is widely used and well-validated. It can be run via the command line or through a web-based interace, and documentation is available covering installation, the algorithm and tips for best practices.

Following alignment, it is essential to manually inspect the output. For typical viral outbreak datasets, alignment visualisation is usually feasible and recommended. This can be done using commercial software like Geneious or through open-source options like the ARTIC Network Sealion software or Jalview.

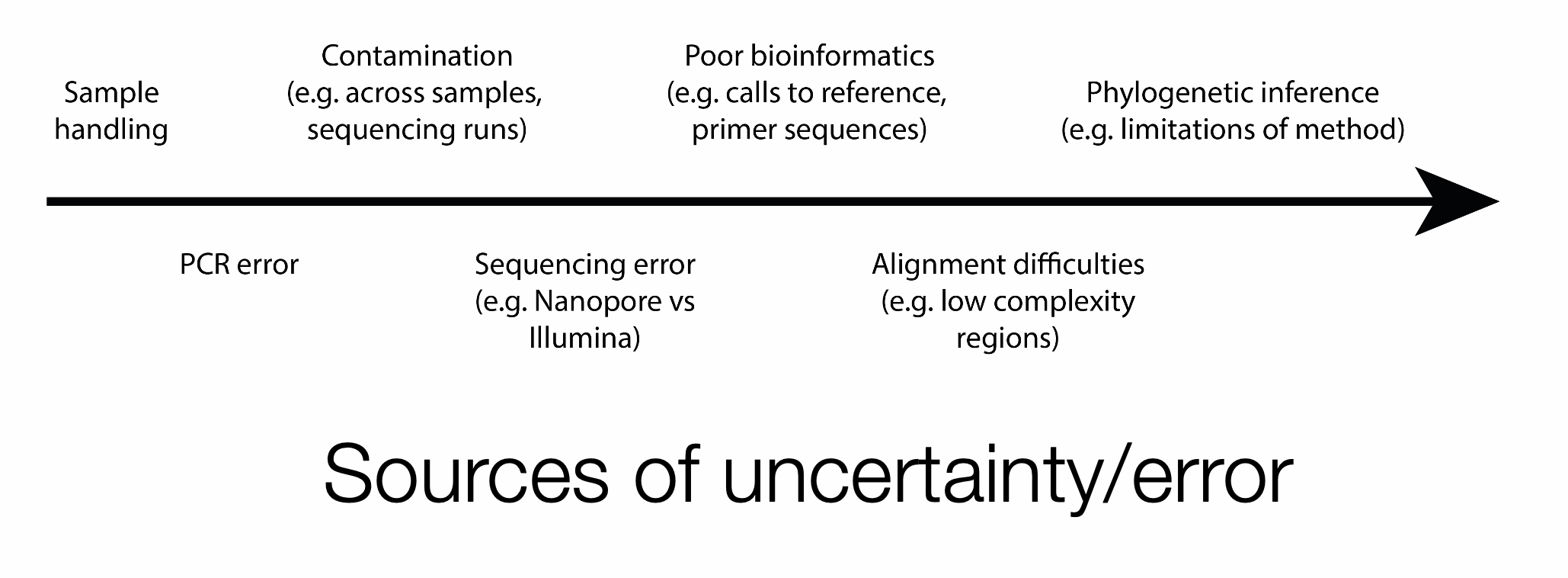

Visual inspection can reveal problematic regions arising due to low complexity regions or low coverage genomes, which can lead to alignment artefacts that we don’t want to take forward into the phylogenetic analysis. Particular attention should be paid to clusters or blocks of mutations that may indicate alignment or assembly arefacts rather than genuine biological variation. Identifying and addressing these issues prior to phylogenetic inference is critical to avoid misleading results.

5. Phylogenetics

Multiple methodological approaches are available for phylogenetic reconstruction. For a comprehensive overview of phylogenetic theory and methods, readers may consult The Phylogenetic Handbook. There are also a number of free training resources online that can help you get to grips with phylogenetic theory. Introductory resources include the EMBL-EBI Phylogenetics tutorial, which gives an excellent overview of the basics of phylogenetic theory, and an excellent series of tutorials on GitHub by mmatschiner.

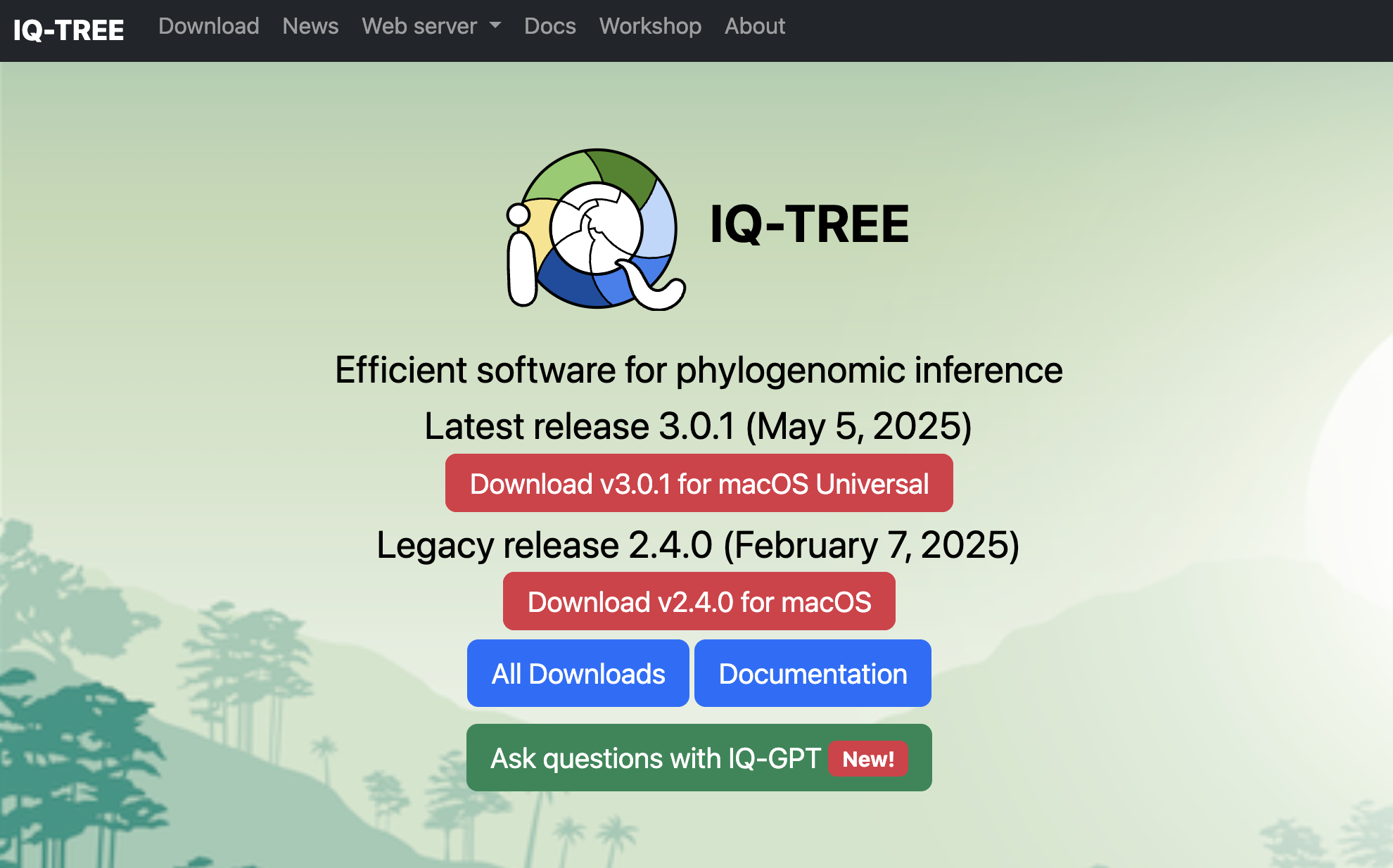

For maximum-likelihood tree reconstruction of viral genome sequences, IQTREE is one of the most commonly used tools and the website contains excellent documentation on how to use iqtree, and the different options available.

For time-resolved phylogenetic analysis, BEAST (Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis Sampling Trees) provides a flexible framework for estimating time-trees and the beast.community website offers many step-by-step guides and tutorials on how to install and run BEAST.

6. Interpretation and reporting considerations

Phylogenetic analyses are most informative when interpreted alongside reliable epidemiological, temporal and geographic data. Genome sequences in isolation are of limited value without accurate and reliable metadata.

Phylogenetic trees should be treated as estimates of evolutionary relatedness, rather than definitive reconstructions of transmission history. Interpretation must take into account the limitations of the data, the analytical approach, and potential sources of error.

When interpreting phylogenies, consider the following questions:

- Does the result make sense?

- Is the observed pattern biologically plausible?

- Could the signal reflect data quality issues rather than true evolutionary relationships?

Results should be interpreted in the context of prior expectations. Unexpected findings should prompt additional interrogation of the data or analysis before drawing unusual conclusions. Particular caution is warranted when inferring importation or directionality of spread.

For MeV, uneven sampling across the globe mean that the genetic diversity available as background context is unlikely to fully capture the global diversity of the virus. In addition, MeV exhibits relatively low genetic diversity due to the genetic bottleneck following the introduction of vaccination, and much of the available genetic data is restricted to the N450 region. Consequently, apparent clustering by country or region may reflect differences in sequencing intensity and data availability rather than true epidemiological linkage. Where possible, phylogenetic inference should be used in conjunction with case investigation data, travel history or other relevant epidemiological information.

When reporting results, it is good practice to:

- Clearly describe the background dataset used for context, including acknowledgement to data generators. Describe any inclusion criterion (quality cut offs) and any known sampling limitations.

- State all software used for alignment and phylogenetics, and the software versions used. For software like NextClade, describe the version of the reference dataset used too.

- Communicating uncertainty transparently and seeking expert input when interpretation is unclear, rather than drawing premature or unsupported conclusions.

For public health applications, phylogenetic outputs should prioritise clarity, transparency, and reproducibility.